Facebook and Wikipedia both improved their total script time by 4% due to various for-in improvements. Note that during the same period, the rest of V8 also got faster, which yielded a total scripting improvement of more than 4%.

In the rest of this blog post we will explain how we managed to speed up this core language feature and fix a long-standing spec violation at the same time.

The Spec

TL;DR; The for-in iteration semantics are fuzzy for performance reasons.When we look at the

spec-text of for-in, it’s written in an unexpectedly fuzzy way,which is observable across different implementations. Let's look at an example when iterating over a

Proxy object with the proper traps set.

let proxy = new Proxy({a:1, b:1},{

getPrototypeOf(target) {

console.log("getPrototypeOf");

return null;

},

ownKeys(target) {

console.log("ownKeys");

return Reflect.ownKeys(target);

},

getOwnPropertyDescriptor(target, prop) {

console.log("getOwnPropertyDescriptor name=" + prop);

return Reflect.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(target, prop);

}

});

In V8/Chrome 56 you get the following output:

ownKeys

getPrototypeOf

getOwnPropertyDescriptor name=a

a

getOwnPropertyDescriptor name=b

b

In contrast, you will see a different order of statements for the same snippet in Firefox 51:

ownKeys

getOwnPropertyDescriptor name=a

getOwnPropertyDescriptor name=b

getPrototypeOf

a

b

Both browsers respect the spec, but for once the spec does not enforce an explicit order of instructions. To understand these loop holes properly, let's have a look at the spec text:

EnumerateObjectProperties ( O )

When the abstract operation EnumerateObjectProperties is called with argument O, the following steps are taken:

- Assert: Type(O) is Object.

- Return an Iterator object (25.1.1.2) whose next method iterates over all the String-valued keys of enumerable properties of O. The iterator object is never directly accessible to ECMAScript code. The mechanics and order of enumerating the properties is not specified but must conform to the rules specified below.

Now, usually spec instructions are precise in what exact steps are required. But in this case they refer to a simple list of prose, and even the order of execution is left to implementers. Typically, the reason for this is that such parts of the spec were written after the fact where JavaScript engines already had different implementations. The spec tries to tie the loose ends by providing the following instructions:

- The iterator's throw and return methods are null and are never invoked.

- The iterator's next method processes object properties to determine whether the property key should be returned as an iterator value.

- Returned property keys do not include keys that are Symbols.

- Properties of the target object may be deleted during enumeration.

- A property that is deleted before it is processed by the iterator's next method is ignored. If new properties are added to the target object during enumeration, the newly added properties are not guaranteed to be processed in the active enumeration.

- A property name will be returned by the iterator's next method at most once in any enumeration.

- Enumerating the properties of the target object includes enumerating properties of its prototype, and the prototype of the prototype, and so on, recursively; but a property of a prototype is not processed if it has the same name as a property that has already been processed by the iterator's next method.

- The values of [[Enumerable]] attributes are not considered when determining if a property of a prototype object has already been processed.

- The enumerable property names of prototype objects must be obtained by invoking EnumerateObjectProperties passing the prototype object as the argument.

- EnumerateObjectProperties must obtain the own property keys of the target object by calling its [[OwnPropertyKeys]] internal method.

These steps sound tedious, however the specification also contains an example implementation which is explicit and much more readable:

function* EnumerateObjectProperties(obj) {

const visited = new Set();

for (const key of Reflect.ownKeys(obj)) {

if (typeof key === "symbol") continue;

const desc = Reflect.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, key);

if (desc && !visited.has(key)) {

visited.add(key);

if (desc.enumerable) yield key;

}

}

const proto = Reflect.getPrototypeOf(obj);

if (proto === null) return;

for (const protoKey of EnumerateObjectProperties(proto)) {

if (!visited.has(protoKey)) yield protoKey;

}

}

Now that you've made it this far, you might have noticed from the previous example that V8 does not exactly follow the spec example implementation. As a start, the example for-in generator works incrementally, while V8 collects all keys upfront - mostly for performance reasons. This is perfectly fine, and in fact the spec text explicitly states that the order of operations A - J is not defined. Nevertheless, as you will find out later in this post, there are some corner cases where V8 did not fully respect the specification until 2016.

The Enum Cache

The example implementation of the for-in generator follows an incremental pattern of collecting and yielding keys. In V8 the property keys are collected in a first step and only then used in the iteration phase. For V8 this makes a few things easier. To understand why, we need to have a look at the object model.

A simple object such as

{a:"value a", b:"value b", c:"value c"} can have various internal representations in V8 as we will show in a detailed follow-up post on properties. This means that depending on what type of properties we have—in-object, fast or slow—the actual property names are stored in different places. This makes collecting enumerable keys a non-trivial undertaking.

V8 keeps track of the object's structure by means of a hidden class or so-called Map. Objects with the same Map have the same structure. Additionally each Map has a shared data-structure, the descriptor array, which contains details about each property, such as where the properties are stored on the object, the property name, and details such as enumerability.

Let’s for a moment assume that our JavaScript object has reached its final shape and no more properties will be added or removed. In this case we could use the descriptor array as a source for the keys. This works if there are only enumerable properties. To avoid the overhead of filtering out non-enumerable properties each time V8 uses a separate EnumCache accessible via the Map's descriptor array.

Given that V8 expects that slow dictionary objects frequently change, (i.e. through addition and removal of properties), there is no descriptor array for slow objects with dictionary properties. Hence, V8 does not provide an EnumCache for slow properties. Similar assumptions hold for indexed properties, and as such they are excluded from the EnumCache as well.

Let’s summarize the important facts:

- Maps are used to keep track of object shapes.

- Descriptor arrays store information about properties (name, configurability, visibility).

- Descriptor arrays can be shared between Maps.

- Each descriptor array can have an EnumCache listing only the enumerable named keys, not indexed property names.

The Mechanics of For-In

Now you know partially how Maps work and how the EnumCache relates to the descriptor array. V8 executes JavaScript via Ignition, a bytecode interpreter, and TurboFan, the optimizing compiler, which both deal with for-in in similar ways. For simplicity we will use a pseudo-C++ style to explain how for-in is implemented internally:

// For-In Prepare:

FixedArray* keys = nullptr;

Map* original_map = object->map();

if (original_map->HasEnumCache()) {

if (object->HasNoElements()) {

keys = original_map->GetCachedEnumKeys();

} else {

keys = object->GetCachedEnumKeysWithElements();

}

} else {

keys = object->GetEnumKeys();

}

// For-In Body:

for (size_t i = 0; i < keys->length(); i++) {

// For-In Next:

String* key = keys[i];

if (!object->HasProperty(key) continue;

EVALUATE_FOR_IN_BODY();

}

For-in can be separated into three main steps:

- Preparing the keys to iterate over,

- Getting the next key,

- Evaluating the for-in body.

The “prepare”-step is the most complex out of these three and this is the place where the EnumCache comes into play. In the example above you can see that V8 directly uses the EnumCache if it exists and if there are no elements (integer indexed properties) on the object (and its prototype). For the case where there are indexed property names, V8 jumps to a runtime function implemented in C++ which prepends them to the existing enum cache, as illustrated by the following example:

FixedArray* JSObject::GetCachedEnumKeysWithElements() {

FixedArray* keys = object->map()->GetCachedEnumKeys();

return object->GetElementsAccessor()->PrependElementIndices(object, keys);

}

FixedArray* Map::GetCachedEnumKeys() {

// Get the enumerable property keys from a possibly shared enum cache

FixedArray* keys_cache = descriptors()->enum_cache()->keys_cache();

if (enum_length() == keys_cache->length()) return keys_cache;

return keys_cache->CopyUpTo(enum_length());

}

FixedArray* FastElementsAccessor::PrependElementIndices(

JSObject* object, FixedArray* property_keys) {

Assert(object->HasFastElements());

FixedArray* elements = object->elements();

int nof_indices = CountElements(elements)

FixedArray* result = FixedArray::Allocate(property_keys->length() + nof_indices);

int insertion_index = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < elements->length(); i++) {

if (!HasElement(elements, i)) continue;

result[insertion_index++] = String::FromInt(i);

}

// Insert property keys at the end.

property_keys->CopyTo(result, nof_indices - 1);

return result;

}

In the case where no existing EnumCache was found we jump again to C++ and follow the initially presented spec steps:

FixedArray* JSObject::GetEnumKeys() {

// Get the receiver’s enum keys.

FixedArray* keys = this->GetOwnEnumKeys();

// Walk up the prototype chain.

for (JSObject* object : GetPrototypeIterator()) {

// Append non-duplicate keys to the list.

keys = keys->UnionOfKeys(object->GetOwnEnumKeys());

}

return keys;

}

FixedArray* JSObject::GetOwnEnumKeys() {

FixedArray* keys;

if (this->HasEnumCache()) {

keys = this->map()->GetCachedEnumKeys();

} else {

keys = this->GetEnumPropertyKeys();

}

if (this->HasFastProperties()) this->map()->FillEnumCache(keys);

return object->GetElementsAccessor()->PrependElementIndices(object, keys);

}

FixedArray* FixedArray::UnionOfKeys(FixedArray* other) {

int length = this->length();

FixedArray* result = FixedArray::Allocate(length + other->length());

this->CopyTo(result, 0);

int insertion_index = length;

for (int i = 0; i < other->length(); i++) {

String* key = other->get(i);

if (other->IndexOf(key) == -1) {

result->set(insertion_index, key);

insertion_index++;

}

}

result->Shrink(insertion_index);

return result;

}

This simplified C++ code corresponds to the implementation in V8 until early 2016 when we started to look at the

UnionOfKeys method. If you look closely you notice that we used a naive algorithm to exclude duplicates from the list which might yield bad performance if we have many keys on the prototype chain. This is how we decided to pursue the optimizations in following section.

Problems with For-In

As we already hinted in the previous section, the

UnionOfKeys method has bad worst-case performance. It was based on the valid assumption that most objects have fast properties and thus will benefit from an EnumCache. The second assumption is that there are only few enumerable properties on the prototype chain limiting the time spent in finding duplicates. However, if the object has slow dictionary properties and many keys on the prototype chain,

UnionOfKeys becomes a bottleneck as we have to collect the enumerable property names each time we enter for-in.

Next to performance issues, there was another problem with the existing algorithm in that it’s not spec compliant. V8 got the following example wrong for many years:

var o = {

__proto__ : {b: 3},

a: 1

};

Object.defineProperty(o, “b”, {});

for (var k in o) print(k);

Output:

"a"

"b"

Perhaps counterintuitively this should just print out “a” instead of “a” and “b”. If you recall the spec text at the beginning of this post, steps G and J imply that non-enumerable properties on the receiver shadow properties on the prototype chain.

To make things more complicated, ES6 introduced the proxy object. This broke a lot of assumptions of the V8 code. To implement for-in in a spec-compliant manner, we have to trigger the following 5 out of a total of 13 different proxy traps.

Internal Method | Handler Method |

[[GetPrototypeOf]] | getPrototypeOf |

[[GetOwnProperty]] | getOwnPropertyDescriptor |

[[HasProperty]] | has |

[[Get]] | get |

[[OwnPropertyKeys]] | ownKeys |

This required a duplicate version of the original

GetEnumKeys code which tried to follow the spec example implementation more closely. ES6 Proxies and lack of handling shadowing properties were the core motivation for us to refactor how we extract all the keys for for-in in early 2016.

The KeyAccumulator

We introduced a separate helper class, the KeyAccumulator, which dealt with the complexities of collecting the keys for for-in. With growth of the ES6 spec, new features like

Object.keys or

Reflect.ownKeys required their own slightly modified version of collecting keys. By having a single configurable place we could improve the performance of for-in and avoid duplicated code.

The KeyAccumulator consists of a fast part that only supports a limited set of actions but is able to complete them very efficiently. The slow accumulator supports all the complex cases, like ES6 Proxies.

In order to properly filter out shadowing properties we have to maintain a separate list of non-enumerable properties that we have seen so far. For performance reasons we only do this after we figure out that there are enumerable properties on the prototype chain of an object.

Performance Improvements

With the KeyAccumulator in place, a few more patterns became feasible to optimize. The first one was to avoid the nested loop of the original

UnionOfKeys method which caused slow corner cases. In a second step we performed more detailed pre-checks to make use of existing EnumCaches and avoid unnecessary copy steps.

To illustrate that the spec-compliant implementation is faster, let’s have a look at the following four different objects:

var fastProperties = {

__proto__ : null,

“property 1” : 1,

…

“property 10” : n

}

var fastPropertiesWithPrototype = {

“property 1” : 1,

…

“property 10” : n

}

var slowProperties = {

__proto__ : null,

“dummy”: null,

“property 1” : 1,

…

“property 10” : n

}

delete slowProperties[“dummy”]

var elements = {

__proto__: null,

“1” : 1,

…

“10” : n

}

- The fastProperties object has standard fast properties.

- The fastPropertiesWithPrototype object has additional non-enumerable properties on the prototype chain by using the Object.prototype.

- The slowProperties object has slow dictionary properties.

- The elements object has only indexed properties.

The following graph compares the original performance of running a for-in loop a million times in a tight loop without the help of our optimizing compiler.

As we've outlined in the introduction, these improvements became very visible on Facebook and Wikipedia in particular.

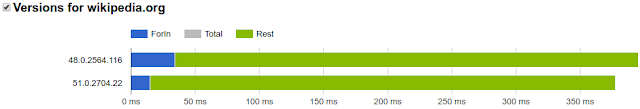

Besides the initial improvements available in Chrome 51, a second performance tweak yielded another significant improvement. The following graph shows our tracking data of the total time spent in scripting during startup on a Facebook page. The selected range around V8 revision 37937 corresponds to an additional 4% performance improvement!

To underline the importance of improving for-in we can rely on the data from a tool we built back in 2016 that allows us to extract V8 measurements over a set of websites. The following table shows the relative time spent in V8 C++ entry points (runtime functions and builtins) for Chrome 49 over a set of roughly

25 representative real-world websites.

Position | Name | Total Time |

1 | CreateObjectLiteral | 1.10% |

2 | NewObject | 0.90% |

3 | KeyedGetProperty | 0.70% |

4 | GetProperty | 0.60% |

5 | ForInEnumerate | 0.60% |

6 | SetProperty | 0.50% |

7 | StringReplaceGlobalRegExpWithString | 0.30% |

8 | HandleApiCallConstruct | 0.30% |

9 | RegExpExec | 0.30% |

10 | ObjectProtoToString | 0.30% |

11 | ArrayPush | 0.20% |

12 | NewClosure | 0.20% |

13 | NewClosure_Tenured | 0.20% |

14 | ObjectDefineProperty | 0.20% |

15 | HasProperty | 0.20% |

16 | StringSplit | 0.20% |

17 | ForInFilter | 0.10% |

The most important for-in helpers are at position 5 and 17, accounting for an average of 0.7% percent of the total time spent in scripting on a website. In Chrome 57 ForInEnumerate has dropped to 0.2% of the total time and ForInFilter is below the measuring threshold due to a fast path written in assembler.

Posted by Camillo Bruni,

@camillobruni